Let’s introduce ourselves to WKCO blog readers. Who are we? Why are we writing about Sufjan Stevens? And this album? It’s (the very last day of) 2025.

Nava: My name is Nava Bahrampour, and I’m a junior at Kenyon from New York City. I have loved Sufjan for quite some time and have tried to find ways to incorporate his music into my Kenyon life, whether it is through writing my first WKCO blog piece about Javelin or singing No Shade In The Shadow Of The Cross with my lovely singing group during my freshman spring. He is one of the artists of my adolescence, my college years and my life in general.

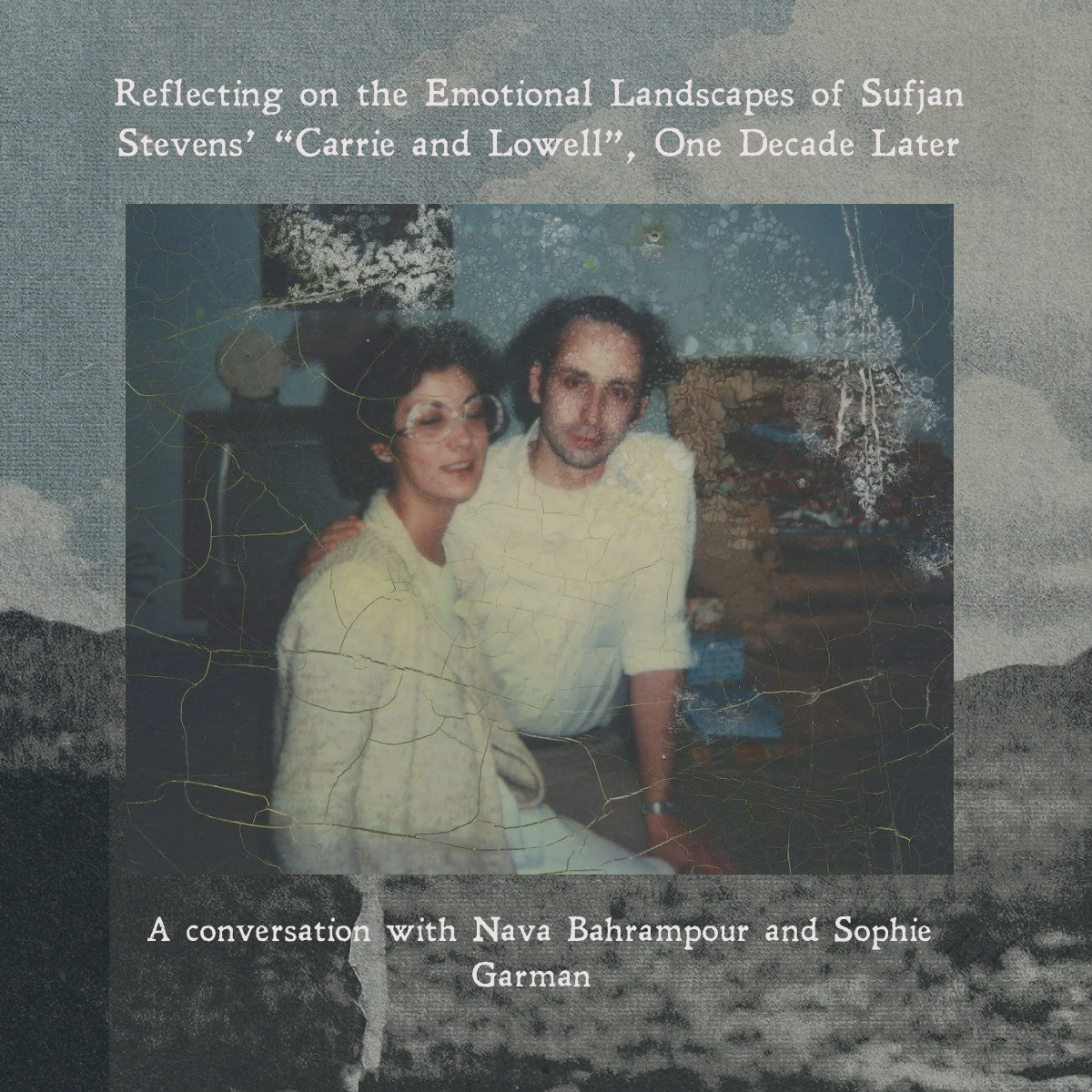

Sophie: My name is Sophie Garman. I’m a sophomore from Newport, Rhode Island. Sufjan Stevens has been one of my favorite artists for a long time, and in May he released a tenth anniversary edition of his 2015 album Carrie and Lowell. The re-release reminded me how much of an impact C&L had on me when I discovered it, and the importance of the album then, now, and forever.

What was your introduction to Sufjan? What does his music mean to you personally?

Nava: I had known about him for a while, but in the middle/towards maybe junior year of high school I got very into his discography. I think I first heard Casimir Pulaski Day (from Illinoise!) which is just a gorgeous and heartrending song and wanted to know everything else after that. His music resonates on so many levels and I find that his lyrics ask questions that I am sometimes afraid to. I am also in love with the universes he builds in his music. In his earlier work (Michigan, Illinois) this was especially apparent; he writes from others’ perspectives with so much empathy, honesty and nuance and makes the narrator, however fictional, feel so incredibly real. He also is fascinated by history and culture and place, and inspires me as a songwriter and articulator of ideas.

Sophie: I first discovered Stevens in about 2020, when I heard Death With Dignity played during the introduction of TV drama This Is Us. I immediately reverse-searched the lyrics on Google, and I listened to Carrie and Lowell endlessly for weeks after. At this point I had just procured my own record player, so, naturally, it was the first physical album I ever purchased. Similar to Nava’s experience of wanting to know everything else, I was determined to discover every project Stevens had to offer, falling in love a bit more with each album I listened to. To me, Stevens’ music is an exploration of his life, something that I think any listener can relate to on some level. He is honest about religion, sexuality, and childhood, and, as Nava observes, asks questions that many of us do not have the courage to.

Favorite track on C&L?

Sophie: I always come back to John My Beloved. Stevens has such a gift for storytelling in a way that is eloquent, but nonetheless graspable for the listener. While he is explicitly meditating on his relationship with a higher power, the lyrics also evoke sentiments of his mother, who is central to the album’s themes, and even perhaps a lover, all with a tender reverence for the subject that is nothing short of heartwrenching. He meditates on his own perceived shortcomings as a “man with a heart that offends with its lonely and greedy demands”. I think this is one of Stevens’ most vulnerable lyrics, and consequently one of my favorites. “Vulnerable” is the most apt word to describe John My Beloved - it is an earnest reflection of his human heart and its desire to reconnect with that which he has lost.

Nava: Absolutely No Shade In The Shadow of The Cross. It immediately stood out to me when I listened to the album for the first time – it’s haunting in its simplicity and structure and I do not think any other songwriter could have written it. To me, it almost feels like the thesis statement of the album, along with the title track. It perfectly articulates the themes of self-destruction, grief, and surrender that are present in Carrie and Lowell. His vocal performance is beautifully delicate here, and the ambiguity in the lyrics make them all the more powerful. Additionally, I have such wonderful memories of arranging and singing it with the Stairwells during my freshman spring at our concert. I also feel like I need to mention City Of Roses, a track that almost made it onto the album. It showed up on his “Greatest Gift” EP that had C&L recordings and cut songs. To me it almost sounds like an epilogue to the entire album.

Where does Carrie and Lowell rank in his discography for you?

Sophie: While I may have a primacy bias, since Carrie and Lowell was my introduction to Stevens’ discography, it is nothing short of my absolute favorite album he has released. The Age of Adz and Illinois hold a special place in my heart, certainly dynamic and masterful in production, but the simplicity of Carrie and Lowell is what draws me to it over and over again. The instrumentals are accessible and pleasing to the ear, which allows Stevens’ poignant lyricism to be the focus of each track. I find that no matter how many times I listen, I always find a new detail within his writing that changes my personal interpretation of a particular track. It is always the album I recommend to friends who want to get into Stevens’ discography.

Nava: I’ll have to say number one as well. Illinois is a close second due to the beautiful, mythological way that Stevens interprets the history of the state, but “Carrie and Lowell” feels the most like Sufjan the person as opposed to solely Sufjan the composer and worldbuilder. Sufjan has always been an apt storyteller, especially in his earlier projects, and I think that he uses those skills powerfully on this extremely autobiographical album. It is timeless and something that I am sure I will love when I am thirty. To me, Carrie and Lowell set a new standard for what the current-day acoustic folk singer-songwriter genre can be. It is accessible but still bold and complex, and never generic.

Track-by-Track Roundtable

Death with Dignity

Nava: Sufjan’s own relationship to religion has characterized much of his early songwriting, from 2005’s Illinois, where the speaker of “Casimir Pulaski Day” wrestles with the complications of faith amidst the death of a loved one to 2010’s The Age of Adz, in which Stevens expresses his desire to “get right with the Lord.” Stevens’ choice to open Carrie & Lowell with this track sets a tone of unfussy vulnerability that defines the best of his work. I have long been fascinated by Stevens’ declaration in the very first verse of the song that “[s]omewhere in the desert there’s a forest and a maker before us.” It’s a testament to the human impulse to make meaning wherever we can find it, to understand our own individual experiences as part of an infinite whole or the result of a higher being. The genius of Death With Dignity is in its rapid switches between minute details – amethyst and flowers on the table, Stevens’ mother’s silhouette, the window of his room – and the song’s large-scale questions of what it means to be alive and “be near” someone whose absence has only further illuminated the complexity of your relationship to them.

Should Have Known Better

Nava: Besides No Shade, this may be my favorite track on the album. I am time and time again surprised and comforted by the interlude. Stevens ends the second chorus wistfully (“oh, be my rest, be my fantasy”) and, this far in the song, one would assume him to be consumed for the rest of the song by the “black shroud” he sings about earlier. However, a synthetic set of major chords hit soon after and Stevens begins to contend with how “nothing can be changed” regarding his relationship with and grief over Carrie, but also the ample opportunity that he has to change his life and outlook. The end of the song finds Stevens grounding himself – and us – in the immediate and sensory. The neighbors’ greeting and the cantilever bridge become tangible buoys and memories amidst abstract, all-consuming fear and sadness, and represent Stevens’ continual plea to himself: “don’t back down.”

All of Me Wants All Of You

Sophie: I find this song to be one of the most complex and interesting on the album, as Stevens draws comparisons between his relationship with his mother and that of an unstable intimate partner. He makes reference to the fleeting nature of his time with his mother, who left him at a young age, as he describes in the previous song. He has very few actual memories of her, mixing his own recollections with myth, as seen in the lyric “in this light, you look like Poseidon/I'm just a ghost you walk right through”, but, in an interview with Pitchfork, he remembers in her a “deep sorrow mixed with something provocative, playful, frantic”, an inconsistent presence whom he still loved unconditionally and who appeared in moments throughout his life.

Drawn to the Blood:

Sophie: One recurring subtheme of religion in Stevens’ discography is his use of Biblical figures and stories to represent people and events in his own life. This song, in particular, references the story of the traitorous Delilah to allude to Sufjan’s desire for people who will ultimately hurt him. Similar to the previous track, he uses language that could pertain to multiple sorts of relationship dynamics; he has explicitly stated that this song is about an abusive relationship, but has not specified whether it pertains to his mother or a lover. This suggests that Stevens is reflecting on a pattern of loving those who will betray him or break his heart, beginning with his mother and continuing into his romantic life.

Eugene

Nava:

Eugene is perhaps the most nostalgic and vivid articulation of Stevens’ grief on the album, alternating between the almost-fantastical (“light struck from the lemon tree”) and the everyday (“the man who taught me to swim, he couldn’t quite say my first name”). Throughout the song, Stevens repeats a throughline, ending most verses with a definitive thesis statement, “I just wanted to be near you,” which eventually shifts to the present tense as he considers these memories some thirty years later. Stevens contends here with the distance (or similarity) between the past and present, and his ultimate admiration and love for his mother being the “best” that is “behind [him].” Stevens does an incredible job zooming out from his own life to ask universally difficult and important questions that resonate with listeners, such as in his recent Javelin single, “Will Anybody Ever Love Me?” – he does this just as well on Eugene, finishing the song with “what’s the point of singing songs if they’ll never even hear you?” This question, of course, is answered by the rest of Carrie & Lowell.

Fourth of July

Sophie: This song is the most well-known from the album, and it is popular for a reason: Stevens’ makes the nuances of the complicated relationship between him and his mother feel as sweet as a lullaby. The sparse instrumentation allows the lyrics to come through clearly, as if he is speaking into the listener’s ear, unmasked by any ornamentation. He seems to be depicting a conversation with his mother, using pet names such as “my little Versaille”, which give the listener an experience of intimacy with and sympathy for Carrie. In an interview, Steven stated that “the whole song, and the interactions and the affections, are all made up, because I didn't have that kind of relationship with my mother. She was very loving and caring and affectionate, but we didn't have pet names, and we weren't intimate.” The heartbreaking nature of this song lies in the fact that Stevens has invented these touching moments to feel closer to his mother after her death. Truly, we often idolize the dead and selectively remember their most tender moments, and Stevens’ admits to this.

The Only Thing

Sophie: On an album that is not afraid to dive deep into grief, having a track that offers hope is one of its greatest feats. This song describes the seemingly “little” ways that Stevens’ faith encourages him to continue living. As Nava said earlier, Stevens’ religion is an intrinsic aspect of his songwriting, and he has said that, while his relationship with God is constantly evolving, his faith is fundamental to who he is. Between the verses, he intersperses sections that address his late mother in the second person, using lyrics such as “everything I feel returns to you somehow/I want to save you from your sorrow”. The Only Thing’s alternation between Stevens leaning on his faith and reflecting on his sadness symbolizes the nonlinear nature of grief. As a listener who is not especially religious, this is the kind of song that makes you understand the objective beauty of faith. Believing in something larger than us is a great comfort for many of us, and it certainly is for Stevens.

Carrie & Lowell

Nava: Amidst mesmerizing finger-picking that calls to mind “For The Widows in Paradise, For the Fatherless in Ypsilanti” from 2003’s Michigan, Stevens relies on minute details to give us a window into the period of time that he spent with his mother and stepfather in Oregon as a child. The most mundane places and things—the backyard, the pear tree—become sacred in this song simply because they are connected to the fleeting summers he spent with her in Oregon. As magical as his memories are, with “[f]airyland all around,” there is a sense of foreboding as Stevens continues describing his youth with Carrie through the world-weary and nuanced but appreciative perspective of his adult self.

John My Beloved

Sophie: I have already spoken briefly about how much I love this song, but it would feel impossible to give it enough praise. There is such rich biblical imagery in this song, which I wanted to explore in more depth. The addresses to “beloved of John” seem to be direct references to Jesus, and he laments upon reading the Bible as “some kind of poem”. In contrast to the consistently hopeful outlook on religion presented in “The Only Thing”, in “John My Beloved”, Stevens is actively questioning and contending with his religious identity following his mother’s death, and utilizes a plethora of metaphors to communicate this in a uniquely Sufjan way. Toward the end of the song, he asks Jesus to “we contend, peacefully before my history ends?” and implores him to “be near me, come shield me from fossils that fall on my head”, acknowledging once again the strength of his faith, which returns to him even when he questions it.

No Shade In The Shadow of the Cross

Nava: Stevens’ unabashed honesty on this track always surprises me, even as a frequent visitor to the melancholic, confessional singer-songwriter universe. Stevens refers to himself as “chasing the dragon too far,” possibly alluding to the self-destructive nature of grief that he has discussed candidly in interviews following the release of Carrie & Lowell. The most impactful moment of this song comes in the form of a vulnerable, pressing confession – “fuck me, I’m falling apart.” The difference between Stevens and his contemporaries can be best explained by Stevens’ unapologetic confrontation of his shortcomings and unruly emotional states in No Shade. Many singer-songwriters suggest that they are just like you in their worst moments; Stevens makes you believe it within seconds of No Shade.

Blue Bucket of Gold

Nava: If I were to arrange all of the songs in Carrie and Lowell to make a cohesive tracklist without previously knowing their order, the album’s original closing track, “Blue Bucket of Gold” would still be the indisputable ending. Blue Bucket of Gold pairs Stevens’ resignation and grief with a stoic and subtly hopeful orientation towards the future. Stevens’ refrain of “raise your right hand / tell me you want me in your life, raise your red flag / just when I want you in my life” coupled with his delicate tenor is possibly the most poignant aspect of the song and a thoughtful meditation on unpredictable relationships that leave us idealistic, grateful for any invitation into the other’s world yet disappointed once we begin to see them more fully. Stevens’ reference to his quest “for things to extol” following his grief is an astute articulation of the rose-colored lens through which he views the past that he refers to in “Eugene” and “Carrie and Lowell.” In “Blue Bucket of Gold,” Stevens continually refers to myths and fables, and suggests that he cannot be impartial to the stories that have been told about his mother. But perhaps objectivity is not the goal of this album. The magic of Carrie and Lowell lies in its subjectivity and in rapid-fire switches between rosy nostalgia and inert sadness. The difficulty in considering a multifaceted relationship like the one he had with his mother requires a certain unbridled hope and idealism, one that does not contradict Stevens’ sadness and grief but coexists alongside it.

Today we visit not only Carrie and Lowell at its original release in 2015, but the 10 year anniversary of the album, which was released this past May. What has changed over the past ten years in the way Sufjan approaches Carrie and Lowell?

Sophie: Ten years after the album was released, it seems that Sufjan feels he is finally able to express his grief without feeling like he has to do it “right”. The fact that he is able to release these raw demos informs us that he is okay with leaving things incomplete, per se. The most notable example of this is “Fourth of July - Version 4”, a thirteen-minute track that features almost ten minutes of ethereal instrumentation, interspersed with the utterance of the original track’s iconic lyric, “We’re all gonna die”. While the intimate story that made the original cut begins the demo version, it trails off into what feels like a dreamlike and unending trance. Sufjan has never been afraid of releasing something that “doesn’t make sense”; why should he rationalize his own grief for his art? Additionally, he included “Wallowa Lake Monster - Version 2”, a demo of a track that had itself not made the original album, as well as a demo version of “Mystery of Love”, a song released in 2017 for the film “Call Me By Your Name”. The inclusion of these two tracks shows that the feelings Sufjan processed while creating “Carrie and Lowell” are not trapped inside that album; they are woven through his discography and inform his art, and his life, as a whole.

Nava: I completely agree; the representations of grief and the “distorted lens” it gives us, that are so central to Carrie & Lowell, have appeared throughout his work following the album’s initial release. I think that, as far as this rerelease goes, he is far more permissive of the unfinished and multifaceted nature of his relationship with Carrie. That being said, I was fascinated by Stevens stating his embarrassment over the record itself in a recent NPR interview. In the interview, Stevens states that, when writing Carrie & Lowell, he “was in the thick of it and… wasn’t thinking clearly, so there’s a lack of objectivity to the music that now feels very foreign and unfamiliar.” I find it interesting from a listener’s perspective that he frames the subjectivity of the album as a lack of clarity, since, to me, Carrie and Lowell is one of the clearest musical and lyrical articulations of human emotion that I have ever heard. It is not “objective,” but its specificity somehow makes it universal. Although grief is a nonlinear process without a neat ending, the existence of the accompanying booklet seems to represent a nuanced yet newly celebratory perspective surrounding Carrie’s life and the years in Oregon that were so central to this record.